A review by RJ Heller

Music is powerful. Faced with a trying situation, even that sometimes maddening memory, when looking for peace we often turn to music. A particular song, composition or even a melody can move one to another place, chase away the turmoil and bring peace.

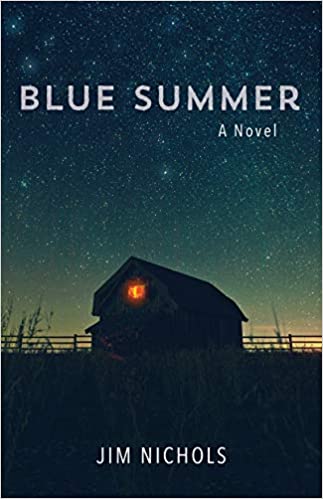

Crafted and expanded upon from a short story, Jim Nichols’ new novel, Blue Summer, joins esteemed work by this prolific short-story writer and novelist. Nichols’ previous book, Closer All The Time, was the 2016 Maine Book Award for Fiction winner. Two previously published novels, Slow Monkeys and Hull Creek, have also received critical acclaim, with Hull Creek finishing as a runner-up for the 2012 Maine Book Awards for Fiction.

Crafted and expanded upon from a short story, Jim Nichols’ new novel, Blue Summer, joins esteemed work by this prolific short-story writer and novelist. Nichols’ previous book, Closer All The Time, was the 2016 Maine Book Award for Fiction winner. Two previously published novels, Slow Monkeys and Hull Creek, have also received critical acclaim, with Hull Creek finishing as a runner-up for the 2012 Maine Book Awards for Fiction.

In Blue Summer, music is the companion on one man’s journey for redemption. Cal Shaw, now a ward of the State of Maine serving time in a correctional facility, sits, writes and reflects on his life. It is a life of circumstance and individual challenge that will test his damaged spirit.

“So I thought I’d try to write this down. Chances are I’m no literary savant, but I promise my heart’s in the right place, and I have been a world-class bookworm for my whole pathetic life, so maybe that’ll help. Who knows? I guess we’ll see.”

It is a fitting introduction and one reminiscent of another book’s opening—that of Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, as Holden Caulfield angrily opens up about “all that David Copperfield kind of crap.” In Cal Shaw, Nichols gives the reader a man humbled by experience who now looks back, accompanied by a melody — a melody that brought him back from the brink and is the same melody that will forever be his companion, bringing him memories of his youth, loss and love. It’s an exceptional beginning and an exceptional book.

Using a first-person perspective, Nichols lets Shaw tell us his story and provides us with not only a narrator but also a friend, a childhood buddy and a taxi-driving, recovering-alcoholic, cornet playing jazz musician to engage with in the process. Cal Shaw is all of that and much more, and Nichols expertly builds upon that throughout the story, adding layers to this man, some predictable and some very surprising.

In a Tampa, Florida, trailer park on the day he thinks may very well be his last, a jazz melody seeps into Shaw’s depressive state and awakens something within him, something he buried from his past. Preparing to end it all, Shaw is saved by that melody that mysteriously finds him. Music can do that, and Nichols knows that, having shared that passion with his father when he was growing up. “I grew up in a house full of music,” says Nichols. “My father was a savant who could play anything that didn’t have strings. He always had a band, where he alternated between piano and trumpet.”

The story, as Shaw reflects, is not linear, but moves back and forth from his childhood days growing up in Baxter, Maine, to his sudden departure and ultimately to his return. Life in Baxter was bucolic until the sudden death of his father. His mother, desperate to provide a life for her three children, marries a man who will undo this idyllic life with vicious abandon and will take more than one life along the way. Looking for comfort, Shaw turns to his Uncle Gus, who becomes his friend and musical mentor. Years later, receiving the news that his uncle has had a stroke, Cal now returns home where he knows the demons of his dreams lurk.

Music is powerful, and so is this story. For Shaw, this melody kept him alive and brought him home. He knew things would be different because of the music. He also knew that he and the music would work things out, together. “Now it’s about Julie and me, about our brother Alvin (yeah, Calvin and Alvin—it wasn’t my idea) and my parents and Becky and that POS Randy Pike and everybody else connected to where I grew up in Baxter, Maine; which means it’s also about tragedy that started during that bluest of summers.”

It’s what Nichols remembers, too, back in the day when he would play with his father. “Dad and I would duet at home on trumpet and trombone. My dad was the classic taciturn Yankee who never said anything emotional but could let it out when he played; I remember after my mother died listening to him play ‘their’ song in such a raw way that it was heartbreaking.” As Nichols explains it, music is more like communicating than remembering, “Sort of like my father communicating his sorrow — when Cal plays Blue Summer he’s talking to Julie.”

Islandport Press, 2020, soft cover, $17.95

Originally published September 25, 2020 in The Quoddy Tides, Eastport

0 Comments