The creak is a distinctive sound— wooden oars kiss the oarlocks, wood rubs green bronze and squeals before it settles into a silent groove. A stroke, pause, water drips and then another stroke. Head moves side-to-side, wary and cautious. A cadence forms between boat and rower.

The trip across the water varies in time, dependent on tide, current and the wind. Weather is friend or foe — no telling which until you’re in it — when rowing off island for food, a doctor’s visit or to take children to school.

For those brave enough to test the waters of an island-bound life today, transit to the mainland is much safer and faster. Power boats make the trip a much easier one, though certainly less dramatic. But before all of that, rowing a dory was the very first chore if one was to leave their island home.

Here along the Downeast coast island living was a unique and hard way of life for many. Lighthouse keepers and their families are the select few now recognized for their bravery and steadfast determination to bring light to the waters along the coast. Many of these stories emanate from isolated spots in dark, cold waters, such as Libby Island Light — celebrated in Philmore Wass’ Lighthouse in My Life and where his family lived for 21 years.

Here along the Downeast coast island living was a unique and hard way of life for many. Lighthouse keepers and their families are the select few now recognized for their bravery and steadfast determination to bring light to the waters along the coast. Many of these stories emanate from isolated spots in dark, cold waters, such as Libby Island Light — celebrated in Philmore Wass’ Lighthouse in My Life and where his family lived for 21 years.

But for others island life is just a day and then another steeped in challenges, wrapped in isolation, comforted by unbridled beauty and cherished as a normal way of life by those who live life on an island today.

According to a State of Maine environment study conducted in 2014, Maine’s waters are home to approximately 4,000 islands. Of those, only 15 “un-bridged” Maine islands have year-round populations. According to the study, Vinalhaven had the largest population and Great Cranberry had the fewest year-round residents.

Monhegan Island was the first island I visited once I found Maine. The island is home to a fishing fleet and artists but still has no automobiles, as it buffers itself against modern ways. What I remember most was a sense of isolation I had not felt before. I was there with other people, but seeing water surround it while hiking its trails instilled a sense of foreboding loneliness in me.

There are islands where generations of families built houses and lives. Starboard Island — now called Ingalls — is accessible via the bar at low tide. Families who lived on the island would take the children by rowboat to attend school on the mainland at the one-room schoolhouse, which still stands today, in the village of Starboard. Ingalls Island is now home to families only during the summer. Foster Island, its concrete castle now gone, has a lone cabin on that spot, and Roque Island, with its rare crescent sand beach, is home to a number of families during the summer months, as well.

There are islands where generations of families built houses and lives. Starboard Island — now called Ingalls — is accessible via the bar at low tide. Families who lived on the island would take the children by rowboat to attend school on the mainland at the one-room schoolhouse, which still stands today, in the village of Starboard. Ingalls Island is now home to families only during the summer. Foster Island, its concrete castle now gone, has a lone cabin on that spot, and Roque Island, with its rare crescent sand beach, is home to a number of families during the summer months, as well.

What makes people venture onto islands to live out their days on a bump in the water? This passage from Philip Conkling’s Islands in Time says it best: “On these islands is an underlying tautness that characterizes much of this lovely coast. It is the tension between rootedness and impermanence, between bounty and failure, between un-giving rock and shifting sand. This cold coast is silent witness to the enduring truth that human enterprise may come and go, may rise and recede like the tide, and that sea and granite alone may endure.”

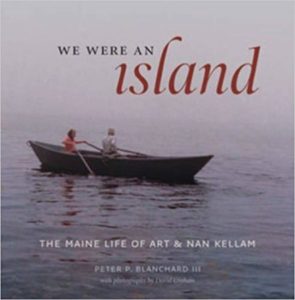

I have recently read about a couple whose choice it was to live on an island. Over time this location proved to be the only place they could have ever lived and been happy. Life is like that, revealing more and providing answers as time moves by.

Art and Nan Kellam lived life on purpose and did so for more than 40 years. That island was Placentia Island off the northeastern coat of Maine, near Mount Desert Island. They found it, bought it and then built a life upon it. “Our first year was one of discovery, in our surroundings, in others, and in ourselves.”— Nan Kellam 1950

The Kellams are gone, but remnants of their life on that island still hover in the air, on the island’s beach and in the fields of grass, rock and trees. The shade of their steps lie all around to be found by visitors from time to time, shared by fauna and flora every single day. The dory they used to row back and forth to the mainland is upside down, its hull like bleached whalebone peeking for its other parts, while slowly sinking into time.

The Kellams are gone, but remnants of their life on that island still hover in the air, on the island’s beach and in the fields of grass, rock and trees. The shade of their steps lie all around to be found by visitors from time to time, shared by fauna and flora every single day. The dory they used to row back and forth to the mainland is upside down, its hull like bleached whalebone peeking for its other parts, while slowly sinking into time.

A life of two became three when Art and Nan set foot on that island. Now the island is all that remains, a family member mourning and remembering loved ones. The island gave, it took, and it demanded respect over time. Like all families, quarrels were inevitable but love was always constant.

When I look to islands today, I see yesterday — island and islanders — looking right back at me. I see pointy spires of trees catch and hold fog as it annoys, gulls floating on bands of unseen air, rocks pummeled by surf, the spray wetting my view.

When I look to islands today, I see yesterday — island and islanders — looking right back at me. I see pointy spires of trees catch and hold fog as it annoys, gulls floating on bands of unseen air, rocks pummeled by surf, the spray wetting my view.

I see the lives of those that chose a life on the island: children play on the beach and wave, clothes hung out to dry wave, too; men fix boats and mend traps, women wrap their arms staring out to the horizon; livestock roam, landscapes are painted, words are written, time stands still and all is good, all is calm, and all is so very perfect.

© 2019 RJ Heller

First published in The Quoddy Tides

0 Comments