“Don’t believe what your eyes are telling you. All they show is limitation. Look with your understanding, find out what you already know, and you’ll see the way to fly.” — Richard Bach

Seagulls are ubiquitous to the coast of Maine. As a boy, seagulls always made me uneasy. I am not sure as to why this feeling settled into my young bones. Maybe it was that Hitchcock movie seen at too early an age, or witnessing the incessant scavenging on a seaside beach one summer and having a gull boldly grab food from my hand. Whatever it was, that uneasy feeling has quietly subsided over the years.

Today I take seagulls in stride and consider them part of the landscape, whether I like it or not. Typically there are many of them, sometimes hundreds, blanketing the Downeast shoreline. To see one all by itself, I would say, is a rare thing. But when afforded that opportunity, a solitary bird soaring or floating on a canvas of blue sky or blue-green waters is a beautiful sight.

Today I take seagulls in stride and consider them part of the landscape, whether I like it or not. Typically there are many of them, sometimes hundreds, blanketing the Downeast shoreline. To see one all by itself, I would say, is a rare thing. But when afforded that opportunity, a solitary bird soaring or floating on a canvas of blue sky or blue-green waters is a beautiful sight.

Whether they are alone or in large groups, it is a foregone conclusion when in the company of wind, sea and land that there will be seagulls to add a poetic touch to a photo, distract from the moment, or harass and annoy anyone sharing the land and water. And let us not forget one particular seagull named Jonathan Livingston. All he ever wanted to do is fly.

It wasn’t until I spent a fair amount of time in Maine did I realize the abundance and variety of these avian vagabonds. I have learned there are three types of gulls in Maine. The great black-backed, which is the largest species of gull in the world, with its stout body, broad wings, heavy neck and bulbous bill; the herring gull with its barrel chest and broad wingspan; and the coquettish ring-billed gull with its medium-size body and slender elongated wings that extend well beyond its tail.

We always told our children when they were young to never feed seagulls. During those long-ago summers while vacationing on the beaches of New Jersey or Maryland, there were always seagulls. Amid the beach-goers with their towels, blankets, and beach umbrellas, were these magician-like thieves of sand-coated French fries, sea-soaked hot dog buns and the occasional stray glob of caramel corn dropped from a child’s hand. All of this and more would eventually find its way into the gullet of a gull. Whatever it is, or in another lifetime was, edible or not, the seagull does not care.

We always told our children when they were young to never feed seagulls. During those long-ago summers while vacationing on the beaches of New Jersey or Maryland, there were always seagulls. Amid the beach-goers with their towels, blankets, and beach umbrellas, were these magician-like thieves of sand-coated French fries, sea-soaked hot dog buns and the occasional stray glob of caramel corn dropped from a child’s hand. All of this and more would eventually find its way into the gullet of a gull. Whatever it is, or in another lifetime was, edible or not, the seagull does not care.

In our early travels to Maine while visiting Acadia National Park, we found ourselves perched high on top of Otter Cliffs. In those days, if you were daring, you could climb and venture pretty much wherever your desire and nerve would allow. The view from atop was great, but I think it was the fact we stepped out of the norm and walked off the trail that made the experience more exciting.

There we sat, ate some snacks, took in the view, snapped photos and relaxed. And then the gull arrived. He soared by; his head cocked our way at an uncomfortable eye-level view. Then we watched as he banked sharply, came back and landed atop the cliff. Cautiously we watched him, slowly pulling our food closer while snapping a photo or two. He was not interested in the food, or us. He seemed to be just taking a break, waiting for the next current of air. Or perhaps he was looking with understanding, trying to find what he knew, and when he found it, was off again in flight to another place.

Thinking of that day reminded me of the book Jonathan Livingston Seagullby Richard Bach, which resonated with me a long time ago. Now, living and writing here Downeast, I think of it often and sometimes remember parts of it whenever I pause to watch seagulls.

“Jonathan Livingston Seagull…was no ordinary bird. Most gulls don’t bother to learn more than the simplest facts of flight, how to get from shore to food and back again. For most gulls, it is not flying that matters, but eating. For this gull, though, it was not eating that mattered, but flight. More than anything else, Jonathan Livingston Seagull loved to fly.”

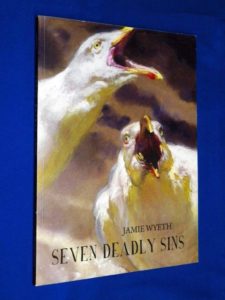

In 2009, Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pa., showcased a collection of paintings by the artist Jamie Wyeth. Early in his career, Wyeth was drawn to the lines and symmetry of the seagull. He studied and painted gulls, and as with many artists, his paintings began with detailed anatomical sketches. Ornithologists marveled at the precision Wyeth was able to capture of gulls in paint. The collection titled The Seven Deadly Sins, was the product of Wyeth’s efforts to place these seven human transgressions onto canvas in the form and imaginative expression of seagulls. Ever since seeing it, whenever I happen upon gulls I cannot help but to think which gull could be gluttony and which could be arrogance.

In 2009, Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pa., showcased a collection of paintings by the artist Jamie Wyeth. Early in his career, Wyeth was drawn to the lines and symmetry of the seagull. He studied and painted gulls, and as with many artists, his paintings began with detailed anatomical sketches. Ornithologists marveled at the precision Wyeth was able to capture of gulls in paint. The collection titled The Seven Deadly Sins, was the product of Wyeth’s efforts to place these seven human transgressions onto canvas in the form and imaginative expression of seagulls. Ever since seeing it, whenever I happen upon gulls I cannot help but to think which gull could be gluttony and which could be arrogance.

I often wonder what the shoreline would look and sound like without seagulls. Would wind and weather, fog and wave, fisherman and sailor miss their hungry counterparts? Would these companions of feather and flight, with their cacophony of lustful sound, gluttonous and greedy appetite, sometimes lazy attitude with a pinch of jealousy, prideful arrogance and oft displayed wrath-like anger all assembled in a robust body with hefty bill, set upon broad webbed feet be missed? Yes, I believe they would.

© January 2019, RJ Heller

0 Comments